The conventional birdwatching is related to a science of identifying unknown birds in the field. Most books on the techniques of bird watching to beginners did convey this scientific approach to identify birds in the field. However with the advancement of the digital camera the theme for identifying new or unknown birds in the field is no longer in practice. Today a digital photograph is compared with an image in the internet or with an illustration in a field guide and the bird is described.

The system of scientific identification however is still practiced in the study of Ornithology and could be described as a methodology for identifying a bird species in the wild through a systematically developed comparison and elimination approach on six criteria. It could be further classified as fitting the observed bird into six predefined modules developed for the country. They are classified as Silhouette…Field markings…Posture…Size…Flight pattern… the Habitat…in which it is seen with the date and time included.

Silhouette

The silhouette in general is the back lit image of a bird viewed in black or very dark grey. This lets you to identify a general group of birds as hawks, owls, parrots, flycatchers, shrikes, storks, etc. whose members all share a similarity. Birds in the same general group often have the same body shape and proportions, although they may vary in size. Therefore the silhouette alone gives many clues to a bird's identity, allowing you to assign a bird to the correct group or even the exact species.

Field markings and characters

In order to describe a bird, ornithologists divide its body into topographical regions; the beak or bill, head, back, wings, tail, and legs. These regions are further divided as in the diagram giving with commonly used descriptive terms.

Birds display a huge variety of patterns and colors, which they have evolved in order to recognize other members of their own species. Birdwatchers also use these features that are known as field markings to help distinguish different bird species.

Beak and Legs

The shape and size of a beak indicates the nature of its food and manner of feeding. Different beak structures have enabled birds to exploit different habitats and fit into a wide range of niches. Distinct beak shapes help identify some bird species, and some shapes help identify some common groups.

The legs though not very visible without a visual aid also relate to posture and habitat. This also could be grouped as branch grasping feet, predatory feet, swimming feet or wading feet. The length, colour and structure of the legs can assist in identification and is a very useful feature in identifying wetland birds.

Posture

Posture or the stance of the bird when on the perch or on ground gives a clue to help place the bird in its correct group. Members of the thrush family would stride across the yard, take several steps then adopt to an alert upright stance with its breast held forward. All thrushes have similar postures, as do larks and shorebirds. This way one could short list the bird to a possible group from the other groupings.

Distant perched crows and hawks may look alike, but paying attention to their different postures will help one to differentiate one from the other

Size

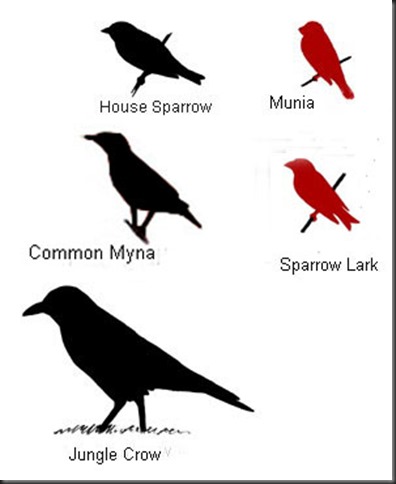

By now the bird is assigned a group based on the silhouette, some field markings and its postural stance. The next step is to do a size comparison of the bird. However the sizing could be complicated at times with poor lighting or the distance to the bird. Size comparisons are most useful when an unknown bird is seen side-by-side with a familiar species. In the case of an isolated bird the sizes is compared with a commonly known bird species such as the House Sparrow, Common Myna, the Jungle Crow, as references.

Equal in Sizes:

A crow-sized pigeon would be a Green Imperial Pigeon and a woodpecker of the size of a sparrow might be a Brown-capped Woodpecker.

Sometimes you need two reference birds for comparison. An Ashy crowned Sparrow Lark bigger than a sparrow but smaller than the Myna. A cuckoo is larger than a Myna but smaller than a crow.Flight Pattern

Most birds fly in straight lines flapping in a constant rhythm, but certain bird groups have characteristic flight patterns that can help identify them. Birds of prey may be identified by the characteristic way they hold their wings when flying toward you. A flying accipiter such as the Shikra or Goshawks would typically make several wing flaps followed by a glide. The eagles and kites soar up in circular motion with the thermal currents and are generally not seen flying until mid-day. Barbets and Woodpeckers generally fly in a pattern of moderate rises and falls. The woodpecker flap wings at the fall while the barbet flaps wings at the rise.

Habitat

In general, each bird species occurs only within certain types of habitat. It could be a dense forest as the Sinharaja, the scrub jungles in the low country dry zone, montane cloud forests in the central massif, and the rolling lands of the lower Uva Patna or freshwater marsh. For instance a given habitat will contain its own predictable assortment of birds and with time one can learn which bird to expect in a particular habitat.

It should also be noted that it is always possible to encounter an unfamiliar bird in a location considered outside its usual habitat. Migrating birds in flight often settle down when they are tired and hungry regardless of the habitat.

This is the general scientific methodology derived to identify a bird species in the field. However the notes taken in the field should be compared with a good descriptive bird guide to confirm the sightings. Viewing distant birds would be assisted by viewing aids; a suitable pair of binoculars or spotting scope. Nevertheless the general grouping of birds could be achieved even without viewing aids.

The other very important rule in the field is that the welfare of the bird comes first and not that of the birdwatcher. World birdwatching bodies have developed birdwatching ethics that are universally accepted and birders need to be self-disciplined in this aspect.

The general factsheet on ethical birdwatching is as below: Promote the welfare of birds and their environment

• Support the protection of birds and their habitat

• Avoid stressing birds or exposing them to danger

• Avoid using methods such as flushing, spotlighting and call playback, particularly during nesting season when birds may be called off incubation duties, or even abandon the nest altogether

• Be aware of the impact photography can have on birds - avoid lingering around nests or core territories for long periods and limit the use of artificial light

• Avoid handling birds

• Report rare bird sightings to conservation authorities and consider the wellbeing of the bird before making this knowledge more publicly available

• Stay on roads, trails, and paths where they exist- avoid leaving litter along a birding trail and otherwise keep habitat disturbance to a minimum

Respect the law and the rights of others

• Do not enter private property without the owner’s explicit permission

• Follow all laws, rules, and regulations governing use of roads and public areas

• Consider and respect the rights of landholders

• Practice common courtesy in interactions with other people

Group Birding Ethics

• Lead by example and know your audience – encourage others to employ ethical birding practices

• Report bird sightings – all data are useful to bird conservation and wherever possible, should be reported to ornithological databases in the country example Universities, Natural History Museums, etc. [in Sri Lanka, FOGSL ]

• Impart knowledge – share what you know about birds and their habitats

• Get involved – encourage birders to engage local communities and get involved in conservation initiatives at their favourite birding locations

• Consider the birds – always put the health and well being of birds first- consider the impact you as an individual and the group are having on birds and their environment

Very interesting and informative.

ReplyDeleteone of the scientific identification, thanks lot...

ReplyDeletePipe Threading Machine

Thanks for information very much useful.

ReplyDelete